World Between Worlds

Greg Martin

Liberty Wildlife Contributor

The descent from day into night, and the reemergence of the sun over the horizon, marks the passing of time wherever you are. In the Desert Southwest, it announces the wholesale transformation of one world into another. The desert by day and the desert by night might cover the same topography, but each is its own universe, with its own denizens, dangers, and opportunities. Brutal summers mean that most animals think twice before braving life beneath the merciless sun; gentle winters, by contrast, bring vibrant landscapes that flush with color as colder parts of the country fade into bleary gray. Sunset signals bedtime for diurnal birds of prey, while owls of all sizes rise to meet the night; they lord over the same terrain like mirror images of each other. An entire subset of Arizona’s Sonoran Desert wildlife patiently beds down to await the darkness, while others seize the chance to get what they need before more dangerous things – snakes and scorpions and coyotes – come out to hunt.

On the fringe lies a twilight realm filled with creatures all its own. Dusk and dawn unite a happy medium between visibility and temperature that allows myriad animals to flourish, if only for a few hours. Among them is a group of avian oddities haunting this transitory period: nightjars.

On the fringe lies a twilight realm filled with creatures all its own. Dusk and dawn unite a happy medium between visibility and temperature that allows myriad animals to flourish, if only for a few hours. Among them is a group of avian oddities haunting this transitory period: nightjars.

There may be no more confusingly named assortment of birds in the world. The Common Nighthawk, for instance, isn’t a hawk, and it distinctly lives a crepuscular, not truly nocturnal, existence. And it hunts more like a whale than a raptor. Following its nightjar kin, the Common Nighthawk loops through the air to feast on bugs, scooping them in with its over-large mouth. They’re both simple to spot and easy to misidentify because while they present a frequent sight in Arizona, they’re known to intermingle with bats. It takes some close observation during the feeding frenzy to realize that one is a bird and the other a mammal, though they’re both out and about for the same purpose. Common Nighthawks go by the nickname “bullbats” for that very reason.[1]

Though not terribly impressive to look at, nightjars possess outsized personalities. Besides their aerial acrobatics, Common Nighthawks are more than willing to fling themselves at territorial intruders, including humans. They funnel wind through their feathers while diving to produce a surprisingly unnerving boom sound.[2]They also have no qualms about feigning injuries to lure predators from nesting sites. It takes nerves of steel to flop around on the ground, hoping to pull away something that’s guaranteed to kill you if it closes the distance before you recover. It’s not the kind of bravado that one would expect from a big-mouthed bug hunter. The reality, though, is that most birds are strictly diurnal, and have no choice but to retreat as daylight fades away. But it should come as no surprise that confidence is one of their strong suits. Spending their lives waiting for the right hour to emerge means a lot of time isolated in comparative vulnerability. Nightjars have no weapons to defend themselves; yet by living a crepuscular lifestyle, they thrive during that rare crossover period between light and darkness that sees predators of all stripes coming and going. It’s a lucrative schedule, but not one for the timid.

Though not terribly impressive to look at, nightjars possess outsized personalities. Besides their aerial acrobatics, Common Nighthawks are more than willing to fling themselves at territorial intruders, including humans. They funnel wind through their feathers while diving to produce a surprisingly unnerving boom sound.[2]They also have no qualms about feigning injuries to lure predators from nesting sites. It takes nerves of steel to flop around on the ground, hoping to pull away something that’s guaranteed to kill you if it closes the distance before you recover. It’s not the kind of bravado that one would expect from a big-mouthed bug hunter. The reality, though, is that most birds are strictly diurnal, and have no choice but to retreat as daylight fades away. But it should come as no surprise that confidence is one of their strong suits. Spending their lives waiting for the right hour to emerge means a lot of time isolated in comparative vulnerability. Nightjars have no weapons to defend themselves; yet by living a crepuscular lifestyle, they thrive during that rare crossover period between light and darkness that sees predators of all stripes coming and going. It’s a lucrative schedule, but not one for the timid.

Ultimately, nightjars go where the insects do: by winnowing away the hordes, they play a crucial role in organic pest control. It’s important to remember that every animal serves its purpose in the larger natural machine. Even the peculiar ones.

Especially the peculiar ones.

[1]https://www.britannica.com/animal/nighthawk-bird

[2]https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Nighthawk/overview

A Book For Any Season

Gail Cochrane

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

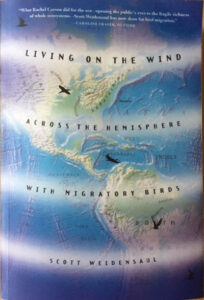

“At whatever moment you read these words, day or night, there are birds aloft in the skies of the Western Hemisphere, migrating. If it is spring or fall, the great pivot points of the year, then the continents are swarming with billions of travelers, a flood of birds so great that even the most ignorant and unobservant notice, if nothing else, the skeins of geese and the flocks of robins.”

So opens Scott Weidensaul’s stunning book Living on the Wind – Across the Hemisphere with Migratory Birds. Weidensaul’s prose is gorgeous and the scope of his topic is immense. He begins his story onsite at the Bering Sea where scores of species summer due to rich feeding opportunities. This is the starting point for migratory journeys that stagger the mind. As Weidensaul notes, birds don’t migrate because of cold weather, but because of food supply, particularly for insect eaters who must reach the tropics to find wintertime meals.

The tiny blackpoll warbler weighs in at one half of one ounce. It breeds across the northern hemisphere from Alaska to Hudson Bay to New England. In fall the Alaskan birds will cross our continent on northwesterly winds and then cross 2000 miles of Atlantic waters to finally make landfall in Venezuela or Guyana. The birds generally travel at night, waiting for the passage of a cold front and then gaining from the brisk tailwinds that follow, traveling at altitudes up to 5000 feet. When the northwesterlies run out the warblers gain momentum from subtropical trade winds. Most blackpolls fly on another 1500 miles to Bolivia or Brazil. In April or May, the birds return to Alaska via a route over the Gulf of Mexico and interior North America. The annual elliptical round trip may cover eleven or twelve thousand miles.

There are birds that fly further. A species of curlew called the bristle thigh flies from Alaska to the South Sea islands around Fiji, motivated and guided by genetically programmed cues. The youngsters are only five weeks old when the parents leave them to fly south. Left behind, they busy themselves putting on fat, gorging on berries and insects. Diminishing daylight hours trigger an instinctive orientation towards the south-southwest and their ancestral wintering grounds. Undeniable agitation sets in and the flock of youngsters takes to the air in short practice flights, testing winds aloft and waiting for the right combination of wind speed and direction. As with other migratory species, the curlews orient themselves with the sun by day and the stars by night. They apparently sense the earth’s magnetic field and perhaps also low-frequency waves generated by trade winds and surf.

“Every rainless autumn night, half an hour after sunset, the land sighs a great, upward breath of birds, which climb to one or two thousand feet before leveling out, their beaks pointed south.” The observation of migration is made difficult by the fact that most birds travel by night, but nocturnal migration is successful for many reasons. It may help birds avoid predators, or free up daylight hours for feeding and rest. Nighttime skies are cooler, preventing overheating in the laboring birds, and damper, reducing thirst. Winds are typically less turbulent.

In a chapter called River of Hawks, Weidensaul documents hawk watching over the Veracruz area of Mexico. Broad-winged hawks, Swainson’s hawks, turkey vultures, and Mississippi kites migrate through in unbelievable numbers. “Watching the migration was a bit like seeing some great, slithering snake, for the mainstream of the flight shifted sinuously from east to west as the day wore on, moving like a sidewinder tossing its looping body across the land – a serpent of hawks that for hours had no head and no visible tail.”

This is a fantastic book, with so much more in-depth information about birds and their amazing journeys. Read it, gift it, be astounded.

Arizona Desert Tarantula

Claudia Kirscher

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

This fall, while out hiking, perhaps you have been fortunate enough to encounter an Arizona Desert Tarantula (sometimes called the Arizona Blond Tarantula for its light brown or tan coloration) that seemed to be marching towards a specific destination or even small to large numbers that appeared to be “migrating”. What you were in fact witnessing were males out searching for females during the July through September mating season. Some can cover 50 miles in their search.

Tarantulas build deep burrows in soil and line the opening with silk webbing which helps to prevent “cave-ins” and can also trap prey. When a male discovers the burrow of a mature female, he will rustle and tap the burrow webbing. If receptive, she will signal her okay to enter. It is a quick mating encounter with the male leaving immediately or he might become a meal for the female. The eggs are laid in the burrow and the hatched young will remain for a while before dispersing.

Tarantulas are members of the Arachnid, or spider family. Worldwide, there are hundreds of tarantula species and some have potent, deadly venom, but the Arizona desert or Western tarantula has weak venom. Although the bite is painful it is mostly harmless to humans. They will bite if harassed or provoked. If it feels threatened, it will rub its abdomen hairs and then flick these barbed hairs onto your skin, which can be irritating.

Tarantulas prefer dry, well-drained soils. In North America, they are ground dwellers. As nocturnal hunters, they feed primarily on insects, small spiders, arthropods, and small lizards. They will actively chase down their prey. Their venom liquefies their prey for ingestion.

Male tarantulas can live 8 to 12 years while the females can live as long as 25 years. The Arizona species reaches a body size of about 3 to 4 inches. The female is a bit bigger and stockier with lighter shades of browns and tans while the male is thinner with more black hair covering his body with reddish color hair on his abdomen.

During the winter months, they go into an inactive state of semi-hibernation or torpor. They will plug up their burrows with dirt and small rocks to help prevent invasion by predators. They survive during the winter on stored fat reserves. If the weather turns warm, they will come out to hunt in winter.

Their predators include lizards, snakes, birds, foxes, and coyotes. A wasp called the Tarantula Hawk will seek out tarantulas in their burrows. This wasp immobilizes the spider with a sting and then lays its egg on the paralyzed spider’s body. The tarantula is then sealed up in a burrow. When the egg hatches, the wasp larva has a ready-made meal.

Some tarantula species are endangered because of habitat destruction and over-collection for the pet trade. Our local species is common and is not currently threatened.

If you are lucky enough to see one of these creatures or witness the phenomenon of their fall mating march, please do not disturb it or be tempted to take it home as a “pet.” Remember, they are beneficial to our environment and part of the fragile balance of nature!

Photo credit and references: desertusa.com, abc15.com, foxnews.com, desertmuseum.org

Kid Stuff

Carol Suits

Nurturing Nature

Let’s meet three creatures that you might see at night. One is a bird, one an arachnid, and the last, a mammal!

Bird: Meet the nighthawk! Did you know a group of nighthawks is called a “kettle”? You might see them around streetlight and yard lights catching insects attracted to the light.

https://www.birdnote.org/search/node/nighthawk

http://www.biokids.umich.edu/critters/Chordeiles_minor/

http://animalia.bio/common-nighthawk

Arachnid: Tarantulas are spiders in the arachnid family. They have two body segments, eight legs, no wings or antennae. Many people think that spiders are insects but they are mistaken since insects have six legs and three main body parts. Also, most insects have wings.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6GhtgFGWNY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xO-JCAJlCnA

Mammal: Bats are flying mammals and can safely fly in the dark using a special skill called echolocation. They make noises and wait for the sound waves to bounce back off objects (an echo), if it doesn’t bounce back then they can safely fly forward. They can tell the distance of various objects by how quickly the sound waves bounce back to them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9FVoTMOorXA