Kid Stuff Wants Super Heroes to Help

By Carol Suits

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

You can be a Super Hero!

Join us for an exciting program on Saturday, January 29th and save nature at the same time

Earn points, get rewards, be a Hero!

To learn more, send an email to carols@libertywildlife.org

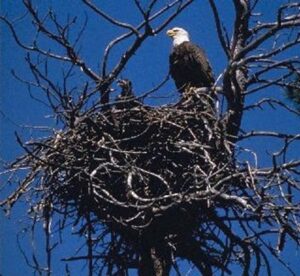

This is the time of year when Bald Eagles start to nest, especially in warmer parts of the country like Arizona, Texas, and Florida. You can watch eaglets hatch and grow while mom and dad take turns feeding and caring for them. Here is a live eagle cam from Florida with two eaglets that hatched recently. Check in on them often because they grow fast!

Look for webcams showing Anna’s hummingbirds and great horned owls. They’re early nesters, too!

Here are some young people who are interested in watching birds in nature. They have binoculars to help them.

First, is an 8-year-old helping people watch for birds.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Zgm55lgCAU

17-year-old Elisa Yang learned that her friends were not interested in birding, so she started her own birding club and made a second group of friends.

https://www.birdnote.org/show/teen-birders

Puzzles!

Courtship in Winter

By Gail Cochrane

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

Resident birds of the Sonoran Desert begin courtship and nesting as early as January. So set aside your hot cocoa and step outside to look for signs of common species wooing and working on nests.

At dusk and before dawn hear the resonant hoots of Great Horned Owls. It’s a bit ironic to listen for this stealthy hunter so silent in flight, but when it comes to courtship GHO’s talk back and forth at great length. You won’t see these owls nest building as they don’t do that sort of work, instead laying their eggs in abandoned raptor nests, on bare ledges of any kind, or on palm fronds.

As the day warms up you might encounter a courting pair of Costa’s Hummingbirds. The male zips 75 to 120 feet into the sky and whizzes back down in arcing loops, emitting a piercing whistle, while the female perches nearby – admiring and yes, judging his prowess.

Curved-bill Thrasher pairs hold a territory throughout the year, defending the area vociferously against intruders. In January you might see nest building activity by these charismatic birds as sticks are brought to cholla, staghorn or other cacti to construct new nests or add to nests from previous years.

You’ll most likely have to get out of town to see Common Ravens. These intelligent birds mate for life, but come winter, the never boring raven male performs impressive aerial stunts to impress his female. He’ll even fly upside down or rolling over while charming her with an array of vocalizations. The flattered female builds a platform nest on a rock ledge, or in a tall tree, with the male assisting by bringing nesting materials, sticks, twigs and shredded bark.

Red-tailed Hawks of the Sonoran Desert also mate for life, staying in an established territory. This male is another awesome flier who woos his female with aerial courtship displays. Red-tailed Hawk pairs have been known to nest in one territory for 20 years.

You may encounter a lovestruck pair of Mourning Doves right outside your door, cooing and nuzzling together before the male scouts out a nesting site. He’ll run this by the female and if she agrees, the two work together to build their flimsy nest. Males assist by bringing materials for females to weave loosely together.

You may encounter a lovestruck pair of Mourning Doves right outside your door, cooing and nuzzling together before the male scouts out a nesting site. He’ll run this by the female and if she agrees, the two work together to build their flimsy nest. Males assist by bringing materials for females to weave loosely together.

Lots to watch for this time of year as you walk about, but don’t forget to scout out some saguaro cacti. High overhead you may spot a Gila Woodpecker working to excavate a cavity nest. This must be done well in advance as the boot needs a couple of months to callus over before nesting begins in late March or early April. By then most all of the bird species will be madly in love and starting families.

Winter And Summer Visitors To Arizona

By Claudia Kirscher

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

On your bird walks or at your bird feeders have you recently noticed new feathered faces ? Many of these snowbird visitors are here in the Valley from colder northern environments including the northern US, Alaska and Canada. The seasonal movement of migration, as the freeze line extends, brings them here.

Birds typically move north to breed in spring/summer areas with increased insect and plant foods, then south in fall/winter to warmer climates with increased food availability. They are also moving to escape the cold although many can withstand very cold temperatures as long as they have an adequate food supply. Some move higher to lower elevations, some medium distances, and some long distances.

There are four major migratory flyways: Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic. Arizona straddles the Pacific and Central, drawing migratory birds from both pathways.

Arizona has a large number of resident birds, here year around, including songbirds, raptors and ducks whose numbers can fluctuate as they move north and south depending on the season. Many do not migrate: Abert’s Towee, Curved-billed Thrasher, House Finch, Say’s Phoebe, Mourning Dove, and Northern Cardinal to name a few resident songbirds. Resident raptors include Bald Eagle, American Kestrel, Harris’, Cooper’s, and Red-tailed Hawks.

Arizona has a large number of resident birds, here year around, including songbirds, raptors and ducks whose numbers can fluctuate as they move north and south depending on the season. Many do not migrate: Abert’s Towee, Curved-billed Thrasher, House Finch, Say’s Phoebe, Mourning Dove, and Northern Cardinal to name a few resident songbirds. Resident raptors include Bald Eagle, American Kestrel, Harris’, Cooper’s, and Red-tailed Hawks.

Birds moving here for spring/summer (and then south for the winter) include Vireos, Summer and Hepatic Tanagers, White-winged Dove, Orioles, Swallows, Swift’s, Warblers, and a big variety of Hummingbirds as well as Turkey Vultures, Swainson’s and Gray Hawks.

We have returning winter visitors such as Yellow-rumped Warbler, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Juncos, Sparrows (White-crowned, Lincoln, Lark, Chipping, Vesper) and Lark Bunting to name a few. Waterbirds include American Wigeon, Northern Pintail, Scaups, Green- and Blue-winged Teal, Canvasback; Snow Goose. There are increased numbers of raptors such as Bald Eagle, Northern Harrier, Ferruginous and Red-tailed Hawks, and Crested Caracara.

We have returning winter visitors such as Yellow-rumped Warbler, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Juncos, Sparrows (White-crowned, Lincoln, Lark, Chipping, Vesper) and Lark Bunting to name a few. Waterbirds include American Wigeon, Northern Pintail, Scaups, Green- and Blue-winged Teal, Canvasback; Snow Goose. There are increased numbers of raptors such as Bald Eagle, Northern Harrier, Ferruginous and Red-tailed Hawks, and Crested Caracara.

Enjoy your feathered snowbird friends now, for in a couple of months they will disappear to the north just as quickly as they seemed to appear in the fall.

Ref: Allaboutbirds, Audubon, Cornell labs, Wikipedia.

Secondary Poisoning

By Greg Martin

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

Pest control poisons are often people’s “go to” response when confronted with animal infestations, whether it’s insects in the kitchen, rats in the shed, or rabbits in the garden. Poisons do one thing: kill. What makes them so popular isn’t just their efficiency at killing, but also their ease of use.

All you have to do is leave poison in the infested area, and sooner or later, the problem will eliminate itself. Effective, yes. Environmentally friendly? Not so much. Without debating the actual use of poison, there is a tremendous risk of collateral damage with any kind of toxic pest control substance. After all, when something ingests poison the poison effectively becomes mobile, traveling inside of the infected animal wherever it goes, until it dies. If a predator catches and eats the poisoned animal, it’s swallowing a biological time bomb that begins wreaking havoc on its own system. In this manner, “rat” poison can easily become “hawk” poison, even when its human user only intended to safeguard his toolshed.

How could something designed to kill small animals affect a large one? In the case of birds of prey, it’s important to remember that raptors weigh much less than their appearances suggest. Even large species, like red-tailed hawks average only around two or three pounds. The biological reasoning for this is obvious: they fly. In terms of predatory efficiency, they’re nothing short of miraculous, packing incredible strength into a streamlined package. Their lack of bulk, though, makes them extremely susceptible to poisons ingested secondhand.

How could something designed to kill small animals affect a large one? In the case of birds of prey, it’s important to remember that raptors weigh much less than their appearances suggest. Even large species, like red-tailed hawks average only around two or three pounds. The biological reasoning for this is obvious: they fly. In terms of predatory efficiency, they’re nothing short of miraculous, packing incredible strength into a streamlined package. Their lack of bulk, though, makes them extremely susceptible to poisons ingested secondhand.

A hawk weighs more than a rat, but not as much as you’d think. If a rat, rabbit, or other rodent that ingests poison doesn’t die immediately, it will become weak and lethargic as it slowly falls victim. A weak, lethargic rodent us a sublime target for any raptor, because weak and lethargic equals an easy meal. Predators are hardwired to seize opportunities like that; they have no way to stop and consider why that rat is moving so slowly. They simply see it, and think, hey, that food’s not moving very fast. It must be my lucky day!

So the hawk catches the rat and devours its meal, in the process ingesting every bit of poison in that rat’s system. What if a dose of rat poison is enough to fatally sicken a rat, but not quite enough to down a hawk? The hawk still has poison in its system. Even if it isn’t potent enough to kill it outright, that hawk will still suffer the ill effects of it, effects that can be deadly for an animal that must operate at peak levels to survive. Any kind of lethargy, or bout of sickness, weakens the bird, and reduces its chances of catching its next meal. Missed meals mean an empty belly, and the onset of hunger only weakens the bird further, stressing it and rendering it even more susceptible to the toxins within. It becomes a sad spiral, each misfortune compromising its system further, until the once healthy hawk is every bit as dead as the rat.

That’s not to say that raptors are the only unintended victims of domestic pest poisons; so are dogs, cats, coyotes, and basically every other predator, whether wild-born or the pet next door. There are cleaner ways to get rid of rats, or any other “pest.” Some are humane, like catch-and-release traps. Others, like snap traps, are at the very least, self-contained. Poisons are made to kill; they can be used so easily, but also spiral out of control so readily.

And when they do, there is always collateral damage.