Imperator

Greg Martin

Liberty Wildlife Contributor

In the year 9 AD, a Roman army met annihilation in the foreboding shadows of the Teutoburg Forest in northern Germany. As many as 30,000 died in that Germanic ambush, a rare and horrific defeat for a burgeoning Empire just entering its prime.[1]Arguably worst of all was the fact that Publius Quinctilius Varus, still infamous in 2019 for having led his force to complete destruction in year 9, lost his eagles.

A life was a life, but those eagles were sacred, and Augustus spared neither time, expense, nor soldiers’ lives in seeking both bloody vengeance and their swift return. Every Roman legion carried an eagle standard, and to surrender such a symbol of Rome’s vitality to an enemy was worse than losing an actual battle: such was the belief of the Romans, and such was the preeminence of the eagle as their symbol. That reverence is not unique to Western Civilization; the eagle is the human ideal of all that is noble and powerful, regardless of culture or continent. The only two eagle species of North America are also its most iconic emblems: the Bald Eagle graces the Great Seal of the United States, its talons bearing both the olive branch and the arrows of war; the Golden Eagle with a snake in its beak is a Mexican icon dating back to the Aztecs, who saw that same bird as a divine sign from their god well before Columbus was even born. They never knew about Rome or its eagles, yet the symbol was to them the same.

Crazy Horse wore a single eagle feather tied in his hair, all the power he needed at the Greasy Grass or Little Bighorn.[2]Eagles embodied just as much for his people and for other groups indigenous to the Americas as they did for anyone in Europe. Mongolians on the other side of the world still hunt on the steppes of Asia with Golden Eagles, just as their ancestors did – and as Genghis and Kublai did – in a tradition of partnership and awe that dates to time immemorial.[3]There are more than sixty kinds of eagle to be found in the world, which makes our North American pair seem rather paltry, in quantity at least.[4]As might be expected, that many eagles invariably leads to some specialized examples, famously illustrated by the Harpy Eagle of South America. This massively strong terror of the treetops boasts almost comically short wings, at least in comparison to its more traditional cousins; in this sense, it resembles the Accipiters of North America, short-winged hawks whose forest environments require hunting at breakneck speeds and with hairpin turns, where even the slightest miscalculation means immediate death. The Harpy Eagle, living in the rainforest, relies on the same concept of movement, even if one of its favorite foods is the happy-go-lucky sloth. Hardly a speed demon to catch, but still: flying through the jungle, especially if you’re the size of an eagle, requires incalculable deftness.

In contrast to its South American cousin, and also to the Bald Eagle that only calls our own continent home, the Golden Eagle of Mexican flag fame is a true world conqueror. This is the bird of the Great Khans, the Holy Roman Emperors, the Russian Tsars, and the Caesars themselves. Theirs is the shadow passing overhead that makes even wolves think twice. Symbols of power, emblems of empires, eagles of all sorts are embodiments of human unity. And that is their most incredible legacy. After all, for all our differences, and for all the distances between us in life and in thought, it says something indeed if people across oceans, across time and across continents, can see the same bird and all think the same thing.

Bird Builders

Gail Cochrane

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

A high level of intelligence allows bird species to design and engineer ingenious nests. Birds instinctively duplicate a pattern copied by every member of their species to create structures where they may safely raise families. In the case of species that build elaborate nests instinct is accompanied by learned behaviors and practice.

The eyesight of a bird affects the type of nest built. Some birds, particularly plant eating waterbirds, have monocular vision; they can’t see out of both eyes at once. These species often nest on the ground, scratching out depression nests. Others like hawks, owls and insectivores that pursue their prey, have binocular vision. Using both eyes together greatly aids in both hunting and in construction of intricate nests.

Raptor species have hooked beaks that rip tissue with great efficiency, but are not the best tools for building complicated nests. Hummingbirds, bush tits and orioles are species that have the intelligence, the equipment (long narrow beaks) and the eyesight to build especially cunning nests.

Raptor species have hooked beaks that rip tissue with great efficiency, but are not the best tools for building complicated nests. Hummingbirds, bush tits and orioles are species that have the intelligence, the equipment (long narrow beaks) and the eyesight to build especially cunning nests.

The young of precocial birds hatch covered in down and with their eyes open. These birds often nest on the ground and the chicks are soon moving about independently. Precocial birds include ducks and quail. Altricial nestlings hatch out naked and with eyes tightly sealed. The parents of these babies must build nests that are well-hidden or high in a tree top, or both, to try and conceal their vulnerable offspring.

Nests are unique to each bird species because of many exterior factors. Diversity of habitats and potential sites, as well as competition among species for nest space creates a rich fabric of variations. Fundamental engineering requirements hinge on the nature of the substrate. Available materials, form, structure and placement must all be considered. Every situation demands a solution to challenges. Barn swallows build fortresses of mud to protect their young. Cactus wrens place their nests in the midst of spiny cholla cacti. Birds like vultures and condors that nest on cliffs do not need to construct nests that are camouflaged or securely woven into trees. They just lay their eggs on the ledge. The eggs of these species must be more conical than round, so if they roll, they roll in circles.

Blueprints of bird nests appear hardwired, as do the movements required to build them. A study of weaver-bird nesting behaviors revealed that young birds repeatedly grasp the sheath of their own feathers and the feathers of other birds in the flock while still fledglings. These grasping motions will be used in nest building when the bird embarks on its first breeding season.

Nest building is an energy intensive effort, often requiring hundreds of gathering expeditions to collect the necessary materials. Young birds polish skills such as finding, cutting and transporting suitable nest materials over time. Scientists have observed that birds show a tendency to collect materials within a certain range of color and size. Green twigs and grasses will be easier to bend, strip and weave than those that have turned brown.Researchers from Ohio Wesleyan University suggest that some birds may select nesting material with antimicrobial agents to protect their young from harmful bacteria.

The nests built by young weaver-birds, hummingbirds and bush tits are crude compared to those of adults.  These builders of complicated nests benefit from practice. Skills that must be mastered to weave intricate nests include the most effective sequences of movement, the securing of twigs, and the dexterity to hold materials with the feet as well as the beak. Birds must also learn not to undo what it has already woven.

These builders of complicated nests benefit from practice. Skills that must be mastered to weave intricate nests include the most effective sequences of movement, the securing of twigs, and the dexterity to hold materials with the feet as well as the beak. Birds must also learn not to undo what it has already woven.

Evolution continues to exert an influence on bird nests. Some birds that live in close proximity to humans have added human structures as potential nest sites. Great horned owls nest on man-made ledges, as do peregrine falcons. In an ever-changing environment, successful species keep coming up with elegant solutions to tough challenges.

Sources:

Bird Nests and Eggsby Pinau Merlin

The Development of Nest Building Behaviors in Weaverbirds. Elsie Collias and Nicolas E. Collias

Evolution of Nests and Nest-Building in Birds by Nicholas E. Collias, Dept of Zoology, Uof Cal LA

Ornithology: Eastern Kentucky University http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/birdnests.html

Is a Bird a Mammal?

(and other interesting bird facts)

Claudia Kirscher

Liberty Wildlife Volunteer

- Even though birds are warm blooded, they are not mammals. They are members of the Aves class. Birds have feathers, wings, beaks with no teeth, and lay eggs. They feed their young by regurgitating partially digested food.

- Mammals (Mammalia class) have hair or fur, give birth to live young, and feed their young with milk from mammary glands. Mammals have paws, hands and hooves. The only mammals that lay eggs are the platypus and the echidna. Their eggs are soft; however, they do have fur and nurse their young.

- The chicken is the most common species of bird found in the world.

- The ostrich has eyes about the size of a billiard ball (larger than its brain).

- A woodpecker does not sing, instead it will drum its beak against a tree or other object. Other woodpeckers can identify which bird it is by the sound of the drumming.

- The bird with the most feathers is the whistling swan, with up to 25,000 feathers. Hummingbirds, on the other hand, are so small that they have fewer than 1,000.

- Male ducks do not quack, typically it is the female who quacks.

- A group of geese on the ground is gaggle, a group of geese in the air is skein.

- The wandering albatross has the longest wingspan of any living bird, 11-plus feet.

- When a hawk has eaten its fill (in falconry terms when it’s “crop is full”) it won’t want to hunt. Another way of saying it’s eaten its fill is to say it’s “fed-up.” The phrase has moved from a bird who doesn’t want to hunt anymore to a person who doesn’t want to do something anymore.

- A falconry hawk has a leash (called a “jess”) to stop it from flying away. When the bird is on the falconer’s arm, he’ll put part of the jess “under his thumb” or “wrap it around his little finger” to keep control of the bird; both phrases have become part of our everyday use.

- Birds can sleep with one eye open and half of their brain awake (called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep) and it allows birds to detect approaching predators while resting. They can also do this while flying during migration.

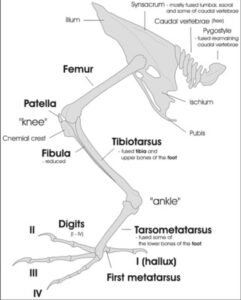

- Though it looks like a bird’s knee is bending backwards, what is bending backward is actually its ankle. Below its ankle is an extended foot bone, leading to the toes. A bird’s real knee is usually hidden by feathers.

Good luck on your next Trivia game ! !

National Geographic; How Stuff Works; Wikipedia; Allabout birds; factretriever

Kid Stuff

Carol Suits

Nurturing Nature

Did You Know?

Watch Bald Eagles on nests incubating eggs and feeding babies. See how to draw an eagle head! But first, learn more about the Bald Eagle.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BEgEIEfSuvU Bald Eagle facts for kids

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cttbjCLCh1w Watch this Bald Eagle mom find the fish that got away!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EUY51PmJB5o – Pittsburgh Hays Bald Eagles on nest. Check to see if all the eggs have hatched!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YYMBJE0xk1sBig Bear Valley, California eagles

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsGZpAHfhGAHow to draw a Bald Eagle head!